Ukraine, Russia, and Global Warming

A topical foray into the intersection of geopolitical struggles and climate.

In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine that began on February 24th, the United States, in conjunction with a coalition of global powers, has imposed a series of economic sanctions. These sanctions take on a number of forms and will impact a wide range of economic activities.

One of the more imposing restrictions is the removal of a select number of Russian banks from SWIFT, a financial messaging infrastructure that connects the world’s banks, allowing for the transfer of money across borders. By becoming barred from accessing the platform, Russia joins fellow authoritarian states North Korea and Iran.

It makes sense to remove Russia from SWIFT. Doing so severely inhibits the country’s economy, limiting trade and foreign investment. It also raises a number of issues, one of which is the dependence of the European Union (EU) on Russian suppliers of natural gas. Currently, the EU imports 38% of their natural gas from Russia.

A portion of this natural gas travels along the Nord Stream 1, an 800-mile pipeline that travels under the Baltic Sea, connecting Russia with Northern Germany. This project is led in part by Gazprom, a state-owned Russian natural gas company.

To date, these sanctions have not affected Nord Stream 1 directly. However, at the behest of President Biden, Germany agreed to halt the licensing process of the Nord Stream 2, a proposed pipeline that would double the supply of natural gas flowing into Europe.

If the construction of the Nord Stream 2 was to move forward as planned, it would solidify the dependence of the EU on Russian energy sources and provide powerful political and economic leverage. Naturally, it is in the best interests of the US and other global powers to limit the extent of Russian influence.

This is also a climate issue. Unlike coal, which generates carbon dioxide as it is combusted, natural gas releases methane when burned. For the first twenty years after it is emitted, the global warming potential of methane is 86 times greater than carbon dioxide. In short, it causes the planet to get warmer more quickly.

Despite this, natural gas is touted as the ‘fuel of the future.’ The strength of this argument rests in limitations associated with the measurement and quantification of methane emissions that occur during the natural gas extraction process. In reality, these operations are continuously releasing methane into the atmosphere, at levels that range from 300-1100 pounds/hour. Estimates place the true quantity of methane emissions at 70% higher than reported values.

In a somewhat ironic twist, natural gas recently replaced coal as the European Union’s largest source of emissions. While these emissions are less than those observed in previous years, they lend support to the positive environmental implications of the Nord Stream 2 economic sanctions.

This rallying cry is often heard within liberal, environmentalist circles in the US. A CNN article written on February 23rd puts this bluntly, stating, “Now Europe — Germany in particular — has an opportunity to use this moment to move away not just from Nord Stream 2 but its growing reliance on fossil gas altogether.”

However, there is no connection between President Biden’s environmental agenda (which has been optimistic at best, misleading at worst), and the sanctions placed on the Nord Stream 2. It is an economic and geopolitical decision.

Unsurprisingly, not all Americans agree with the sentiment expressed by CNN. Dan Crenshaw, a Harvard MPA and former SEAL who currently represents the notoriously gerrymandered second district of Texas in the House of Representatives, used the Nord Stream 2 sanctions to argue for US energy dominance.

Crenshaw is entirely unconcerned with global warming, focusing on what he calls ‘geo-strategic’ lessons that need to be learned in the wake of the Russian attack. To his credit, if the US solidified their position as the world’s energy provider, it would work to address the nation’s widening current account deficit and promote economic growth.

It is worth noting that American oil and gas dominance is possible. Despite the constant framing of these energy sources as ‘non-renewable,’ the reality is that advancements in extraction techniques have allowed American companies to extract previously inaccessible resources. Presently, the US commands the world’s largest recoverable oil reserves.

Bluntly, this is a frightening prospect. With the EPA’s ability to regulate a wide range of emissions sitting at the feet of the Supreme Court, American energy dominance has the potential to push the world past a series of irreversible tipping points.

While we are likely to hit these thresholds regardless of which global power controls the energy markets, the continued use of oil and gas in the EU only serves to speed up the pace at which they are reached.

The last, and perhaps most interesting interaction of climate and conflict, are the effects of the Russian invasion on Ukraine nuclear power plants, which provide the country with 55% of its energy.

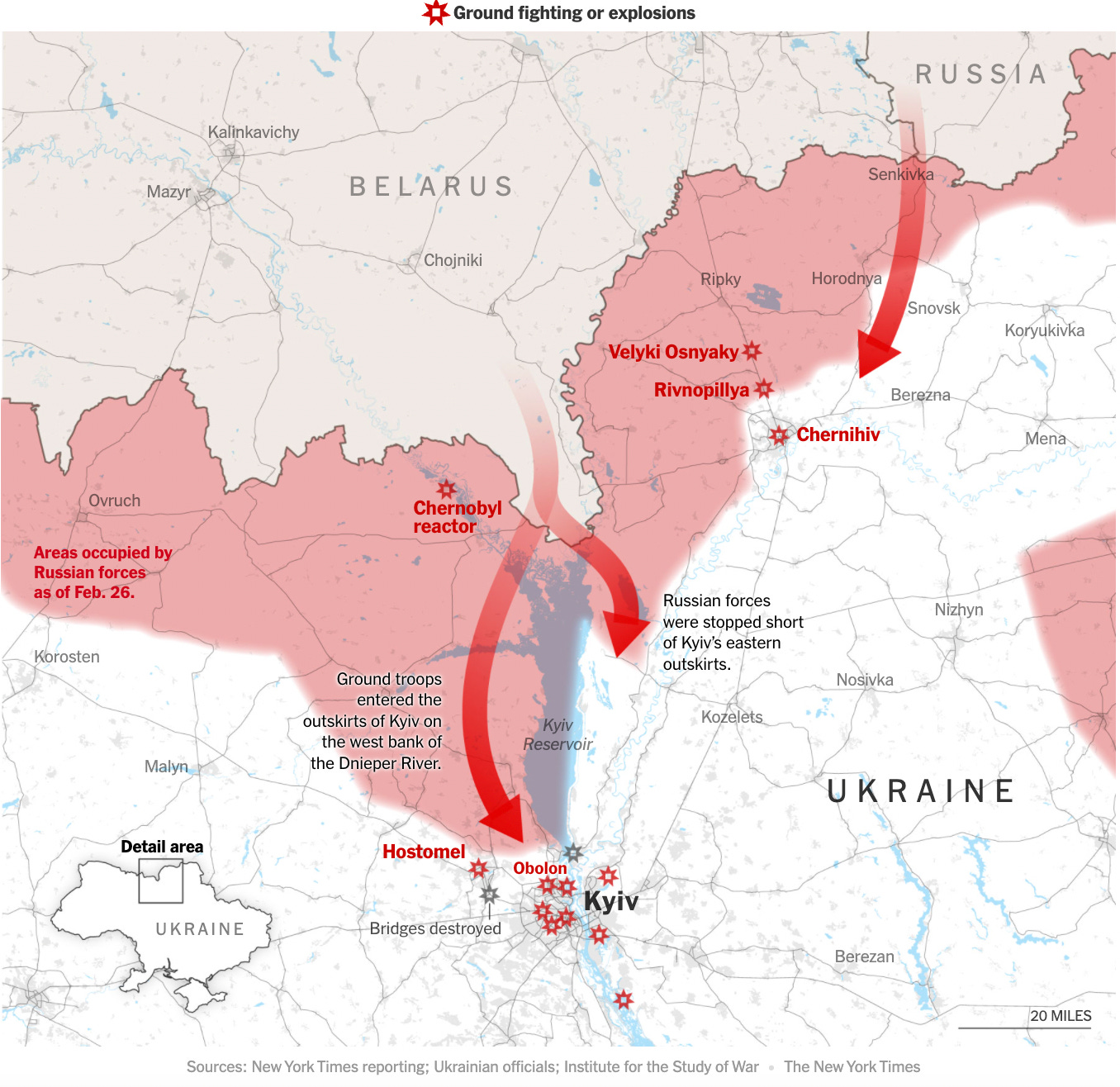

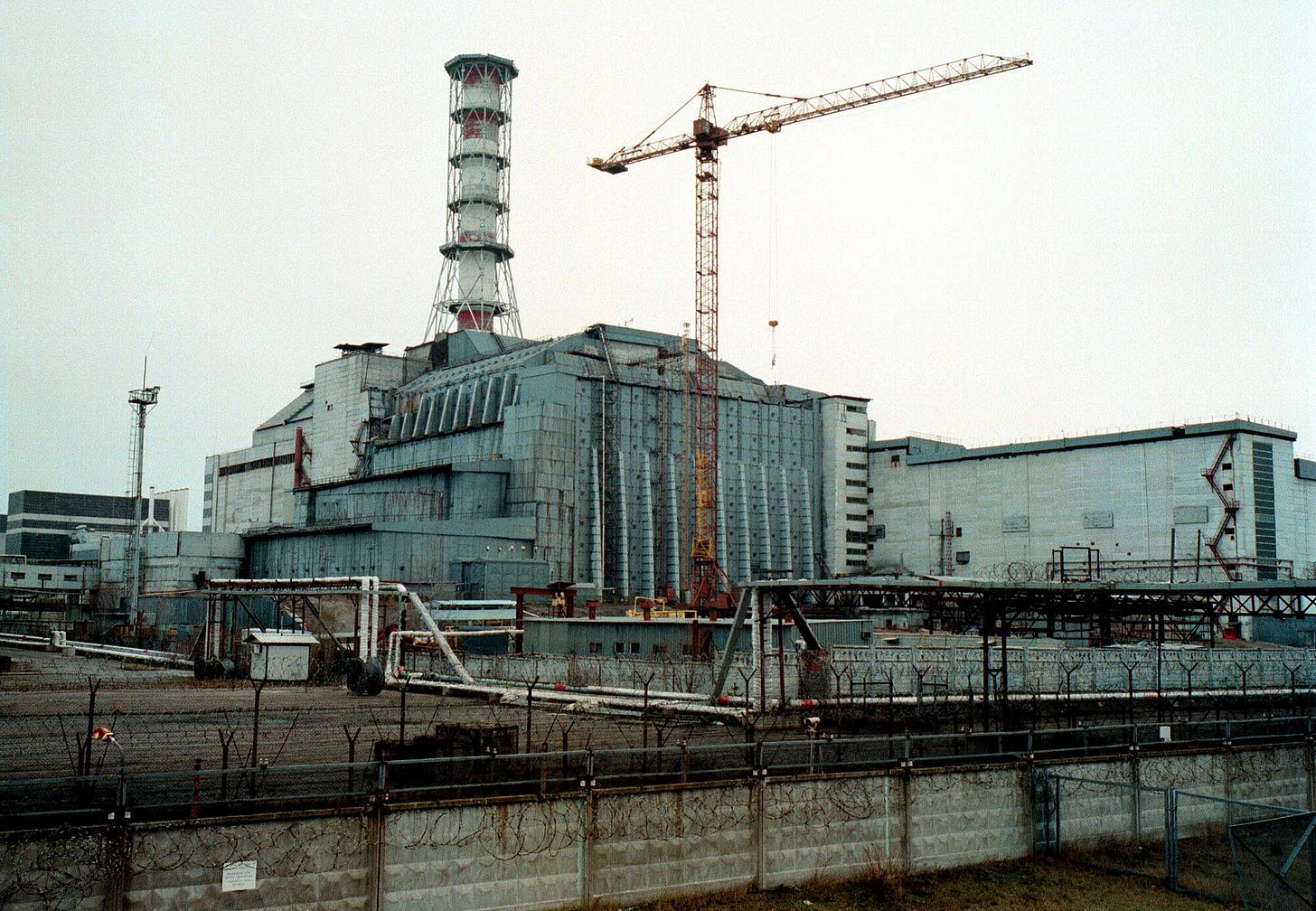

Following their passage across the Belarusian border, Russian troops engaged with local Ukrainian forces, seizing the now-defunct Chernobyl power plant in the process. In the wake of these conflicts, the radiation levels at the site increased by a factor of twenty, a result of increased disturbance that has likely raised clouds of radioactive dust.

In areas where there is no direct access to fossil fuels, nuclear power is cheaper than coal. However, it seems counterintuitive to draw energy from a source that could be used to the benefit of geopolitical rivals in the event of an invasion.

This is a powerful disincentive, carrying a number of cascading effects. Small states could increase investments into renewable energy sources, but issues with establishing a baseline level of power and a lack of energy storage (not despite innovative options) make this strategy unappealing. Alternatively, the US could increase their dominance in global energy markets, offering low-cost, reliable sources of carbon-intensive energy sources. While this would mitigate the dangers associated with energy consumption and geopolitical conflicts, it could be the final nail in our collective, human coffin.

I have no idea what will happen. Clearly, the climate crisis is not as simple as taking greenhouse gasses out of the atmosphere.

Hopefully, these stories work to impress that the climate crisis is multi-faceted in multiple ways (I understand that this sounds redundant, but bear with me). It is the combination of a number of environmental and human-driven processes, the latter of which often affects the former. It is an issue that spans human rights, international politics, and the interests of billion dollar multinational conglomerates. Individuals within the same country, or even the same body of legislature, interpret the effects of the crisis differently, leading to differing responses that carry massive consequences.

Note: Natural gas is the same thing as gas. The ‘natural’ aspect is essentially the same thing as saying ‘natural’ coal or ‘natural’ dirt. It is meaningless and carries no implications as to the environmental impacts of the fuel source.

Really like the addition of links to sources. Well done!

Very well presented and comprehensive.